The Destination Marketing Organization, or DMO — also known in some cities as the Convention and Visitors Bureau (CVB) — looks after the travel marketing and communications of a territory, municipality, or region. In most cases, a DMO represents a variety of industry stakeholders, such as accommodations, transportation, restaurants, festivals and events, attractions, shopping, spas, and meeting planning facilities and providers. As such, destination marketing is a vital component of the travel decision and purchase funnel for consumers as they plan their next vacation or business trip.

Both the New York City’s public/private tourism promotion company NYCGo and the San Francisco Travel Association recently announced they had reached agreements with Booking.com, an online travel agency (OTA), to have it openly provide the transactional engine on their official websites.

Both the New York City’s public/private tourism promotion company NYCGo and the San Francisco Travel Association recently announced they had reached agreements with Booking.com, an online travel agency (OTA), to have it openly provide the transactional engine on their official websites.

Could this mark the beginning of a new and lasting trend?

Why hotels pressured DMOs to offer transactional services

In the earlier days of the internet, circa 1995, travel distribution, website development and transactions were still grouped in the hands of a chosen few global distribution systems (GDSs), such as Apollo, Worldspan and Amadeus — legacy systems that had been developed by airline carriers. Hotels and car companies developed their own central reservation systems (CRSs). Yet there was very little to be found at the destination level, as it proved difficult to have all these systems talk to each other.

Even though the travel industry was among the early adopters of e-commerce and its potential, the hospitality world was led mostly by the work of global hotel brands such as Marriott, IHG, Starwood and Hilton, along with some boutique hotels in niche markets.

Most hotels — in particular, independent brands and smaller inns — were left behind struggling to simply have a web presence, let alone have a transactional component.

It’s within that context that many DMOs chose to develop their own reservation systems, often at very high costs, so that visitors to their destination websites would convert into flights, room nights and other reservations prior to reaching the destination.

Often, the pressure was coming from hotel members who wanted to have an e-commerce option through the DMO, if they could not afford to develop one for themselves.

The rise of the OTA

Expedia was among the first OTAs to quickly make serious in-roads and to build partnerships with key industry players. I recall the early 2000s, while working at VIA Rail Canada, where packages offered on Canada’s passenger rail company’s website were provided by Expedia.

It was a simple and efficient way to extend the brand’s offering (transportation) with what travelers might be seeking once at the destination: hotel, rental car, etc.

In fact, between 2000 and 2010, OTAs became a force to be reckoned with, as they virtually were left alone to develop their strategy and tactics. They invested in state-of-the-art user interfaces that responded to customer needs, with ease of navigation and transactional processes.

Quick to go mobile

OTAs were also among the first to understand and embrace the mobile shift in travelers’ purchase behavior, developing applications for smartphones and others specific to tablets, with various upgrades in the past two years.

The end result? The average consumer now usually books through one of the two major OTAs: Expedia Inc., with its subsidiaries Hotels.com, Hotwire, Trivago and Venere, not to mention its recent agreement with Travelocity; or Priceline Inc, with its subsidiaries such as Booking.com, Kayak and Agoda. In of itself, this is not a problem, per se.

OTAs play a role in the distribution channel, just like travel agents once did (and still do, but to a much lesser extent), and just like tour operators and inbound agencies, or receptives, that can play a role in particular when dealing with international, more complex packaged-type itineraries.

And so just like other players in this distribution model, OTAs take a commission that can vary anywhere between 12 and 25% — sometimes up to 30%, once you buy into “premium” positioning, or a preferred ranking when customers search a given city, for example.

In this sense, OTA also play a role in promoting hotels, a phenomenon known as the “billboard effect” whereby customers will see a hotel on the OTA site, then check out and perhaps book directly on the hotel site.

The French rebellion

For many smaller hotels, the proportion of bookings coming from OTAs has taken a disproportionate importance in the past 18 months. In some cases, hotels who once had 70% of their online bookings come through their own website, with 30% coming from OTAs, saw this ratio reversed in less than 12 months. It must be added: online bookings did not increase year-over-year. It was merely a shift in the distribution source!

Facing some clauses that were judged anti-competitive, French hotel unions (syndicats) recently fought and won a judgement on the controversial issue of rate parity, in which OTAs require by contract that rates must be the same everywhere, in every channel, including a hotel’s own site – thus forbidding hoteliers the right to promote last-minute offers, for example.

Upcoming rulings are expected as well in the UK and in Germany, and even a recent article in Forbes addressed this particular point.

Beyond this recent ruling, over 1,000 independent hoteliers have joined the Fairbooking movement, grouping together and seeking to educate French travelers to the virtues of booking direct. In France, a site like Booking.com is seen as the Devil reincarnated, with various sites, blog posts and recent travel trade reports shunning its dominance in the travel distribution landscape. (In Germany, many hotel owners are also trying to circumvent the major OTAs.)

Yet of all of that hasn’t stopped consumers from using OTA sites in droves.

What role for the DMO?

It’s against this backdrop that recent announcements present a provocative trend. DMOs traditionally would develop their own transactional solution, at high costs and, most often than not, with average to poor results. Now they’re giving up.

Earlier this summer, the small regional tourism office of Eastern Townships, in the province of Quebec (Canada), stirred up a storm announcing it was going ahead with Booking.com as its partner powering a transactional solution for visitors to its website.

With New York City and San Francisco doing just the same thing, who will be next? And will Expedia stay on the side track and watch Booking reap all the public spotlight? Most likely not. At the end of the day, the real question we need to ask regarding this upcoming trend is whether it’s good or not for the client, good or not for the hotel industry, and good or not for the DMO.

Is it a win-win-win? You tell me…

The traveler

For travelers used to going to a DMO site and seeing interesting and aspirational information, having a transactional component powered by an OTA should be a win, since these sites tend to convert more, due to their slick platform and efficient filters. Verdict: Win.

The hoteliers

Many online travelers tend to go a DMO site to gather information about a trip, then will visit hotel sites and/or OTAs before booking. In this context, having the customer convert from the DMO site is great in theory, but it takes away the possibility of direct bookings for those hotel members who have transactional and mobile-optimized websites if the conversion took place on the DMO site.

For smaller hotels that don’t have a transactional component on their website, it may appear at first glance as an improvement, but it will delay their need to eventually have transactional capabilities, while postponing the benefits they could reap from having a relationship marketing strategy in place, capturing client data and so on. Verdict: Lose.

The OTA

Fairly obvious: Booking.com and friends are the clear winners in this new trend, as their brands will reach new audiences and will gain credibility with its association with powerful and known travel brands. Not to mention the de facto distribution exclusivity it gains in these markets when sites like Choose Chicago deal with Orbitz, for example. Verdict: Win.

The DMO

Finally, one could advocate either way about how the DMO wins or loses in this new equation. By not having to invest in an in-house solution, nor maintain yearly costs, it’s a clear win. There is also a revenue-sharing scheme involved in these recent announcements, where the DMO will earn at least 3% of the booking, and as much as up to 50% of the commission (which is rumored to be the deal with NYC) earned on every transaction. Verdict: A clear win, if such is the case.

DMO challenges

Yet if you take the purist view that a DMO ought to represent all its accommodation members, those with and without a transactional site, partnering with an OTA can be seen as a form of resignation in front of today’s competitive distribution challenges.

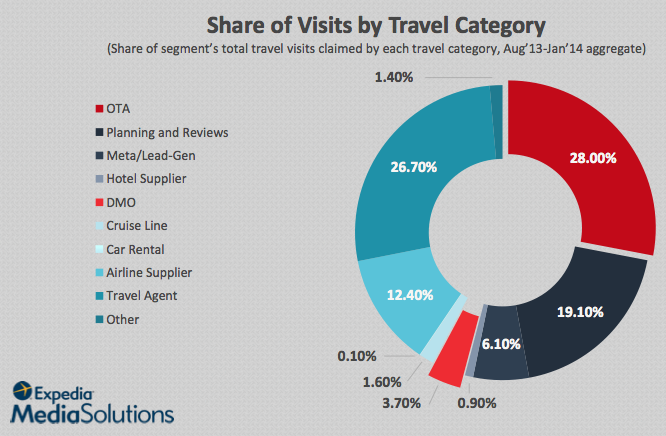

A recent study by Expedia Media Solutions shows how complex the travel package booking can be, with consumers visiting up to 38 websites in the 45 days prior to purchase!

Thus, what role should the DMO have in this moving distribution landscape? Should it partner with an OTA, offer it own in-house solution or simply transfer its web traffic directly to hotel partners of the destination?

I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments section below.

Feedback

This article was originally published on Tnooz. Interesting comments were also made directly on their site, as well as by email. I thought I would share (with his permission) the viewpoint of Tom Rickert, Executive Vice President at JackRabbit Systems:

Leave a Reply